Your Posture is the Practice: An Interview with Hope Martin

By Debra Hiers //

A great way of working with the body in meditation is the Alexander Technique, a process that enhances body awareness. This subtle yet powerful modality offers a way to be more relaxed and comfortable in your body by teaching you to recognize and let go of postural habits that cause discomfort and that distance you from being fully present in your life. It is communicated through a teacher’s verbal and gentle hands-on guidance, but ultimately teaches you how to be your own teacher and apply the principles for yourself.

Hope Martin began taking Alexander Technique lessons in 1980, and completed a three-year training program in 1987. Shortly after that she participated in a month-long meditation intensive and found that even with her extensive Alexander training, she still had “a lot of trouble sitting, a lot of burning in [her] back, a lot of pain and discomfort.”

She knew from her own experience the obstacles people encounter sitting on a cushion or chair for extended periods of time. “When you’re sitting, and all you can sense is your own physical pain, it makes it very difficult to meditate,” she offers. Martin has spent 30 years bringing the Alexander principles to meditation practice and teaching that to others. It is one of her greatest satisfactions to introduce people who meditate to the Alexander Technique.

“One of the reasons the Alexander process fits so well with meditation,” says Martin, “is that it cultivates awareness of how we interfere with our innate ability to be upright, balanced, and at ease. In meditation we are noticing how we interfere with our inherent capacity to be awake and fully present. Since there’s no separation between mind and body, letting go of bodily holding patterns while meditating makes the practice so much more personal and experiential, and brings tremendous ease to sitting.”

Our posture is molded by the way we habitually hold ourselves, formed over time by an accumulation of our many responses to life’s experiences and challenges. “Our responses have become our shape,” she says. “Learning to pause and make different choices, changes the patterns that keep us tense or in discomfort. When you change your responses, your body changes and so does your life. Alexander teaches you to let go, lengthen, expand, and be supported.”

“You could say that your posture is the practice, that being in your body is the practice. It’s a complete expression of what is going on in your mind. When I am discursive while practicing, I notice that I tend to lean into the thoughts. That has a particular shape and quality in my system. The willingness to come back to being more upright, more balanced and supported — what I call downright/upright — is the willingness to come back to the present moment. Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche called it ‘good head and shoulders.’ ”

“A lot of us, when we sit in meditation, don’t know how to be in a vertical orientation. Our habitual patterns are so strong we don’t know that we’re leaning back, leaning forward, or leaning to one side, yet those tendencies produce discomfort and a tendency to be caught up in ourselves. Our habitual patterns are our default setting; we go there without knowing it. In this practice, we’re shifting the default setting from our unconscious habits that have our particular stamp of identity on them to a ‘neutral’ that’s less dictated by our habits and in line with the intelligence of our structures. We learn to stop holding ourselves tight, and to let the earth support us and the space all around us to be our home.”

“When you’re upright, supported and at ease, you have direct contact with your life in the present moment. The tendency we have to sink and be preoccupied with our thoughts is a way of interfering with this fluid, dynamic presence. So, when you come back to the present moment with an awareness of letting go of holding patterns and inviting the balance and ease of your body, there is subtle flow, energy and movement that expresses being alive. By not fixing or freezing experience, you are present right now. This is a personal, direct experience of impermanence.”

Martin points out that holding what you consider a perfect posture causes as much interference as slumping. “Trying too hard always produces rigidity and tightness and it affects your practice adversely,” she says. “So the idea is to get balanced and to quit working so hard, to relax into the present moment, and to receive support from the ground.

“Instead of doing more, we’re encouraged to let go of what we’re doing that gets in our way. The basis of it is to learn to stop trying to change, which always results in working hard and pushing. Pushing does not result in the freedom we are after. So there’s an emphasis on letting the nervous system rest, getting to know our habits and then letting them unwind through an indirect approach that is initiated by the re-balance of the head on the spine.

“If we constantly push, we never find true change. We just substitute one habit (the heavy, slumpy habit) for another (the rigid stiff habit). If we employ habits to change habits we stay stuck in known outcomes. The approach is training for all aspects of our lives – creative pursuits, relationships, our jobs, our meditation practice!

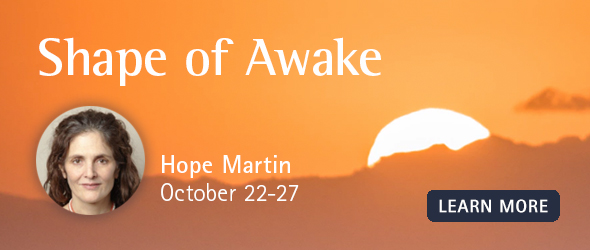

“In The Shape of Awake retreats I lead, we have time to get to know our habitual patterns and make lasting changes. The hands-on work gives an experience of a more supported and movable way of being in your body. Being stiff and held interferes with that. There is subtle movement that happens all the time and you don’t have to interfere with it. The more you allow the transfer of weight to move though your skeletal structure into the earth without collapsing, the more freedom there is.”

I am beginning to sense the profundity of what Martin is talking about and why so many individuals who have worked with her say their practice has been transformed by what she is teaching. Hope explains, “When you have this kind of training it feels good to sit because you’re not fighting with your practice by collapsing or holding some shape you think you should be in. Instead, you make contact with yourself.

“If you have spent your life shrinking and holding your body, making yourself small — if you have lived your life that way, then when you sit on a meditation cushion you have to actually deal with that habitual pattern. Your muscles are used to holding you in a certain way and when you change that, you’re shifting your perception and your whole relationship to your life. It actually shifts things on the level of your own personal karma. It’s the same thing for someone who is all pushed out into the world. They may be overly upright, held and lifted. For them to soften that and melt the armor and to let the ground support them – that’s huge. It’s beautiful. What I see in the shrine room when people start to get the hang of this is that they are so much more present and soft and heartfelt. They change — they change into who they are.”

The process brings an experiential appreciation of how our bodies hold our lives. Hope refers to it as a process of deeply befriending ourselves. “The patterns can only unwind when we make a friendly relationship to what is living inside us, rather than trying to change.” says Martin. “It’s not just about having a good posture on your cushion. You will learn that, too, but you will also become intimate with strong habitual patterns and soften to them in a way that transforms them. It’s a very beautiful process.

“You’re a biped. You’re supposed to be upright. That’s your human birthright. Not interfering with that is an expression of your unconditional confidence and dignity – of being awake, alive, and appreciative of your life.”

A version of this article originally appeared in Shambhala Times in 2012

About Hope Martin