The Shamatha Project, Part II: Collecting Data

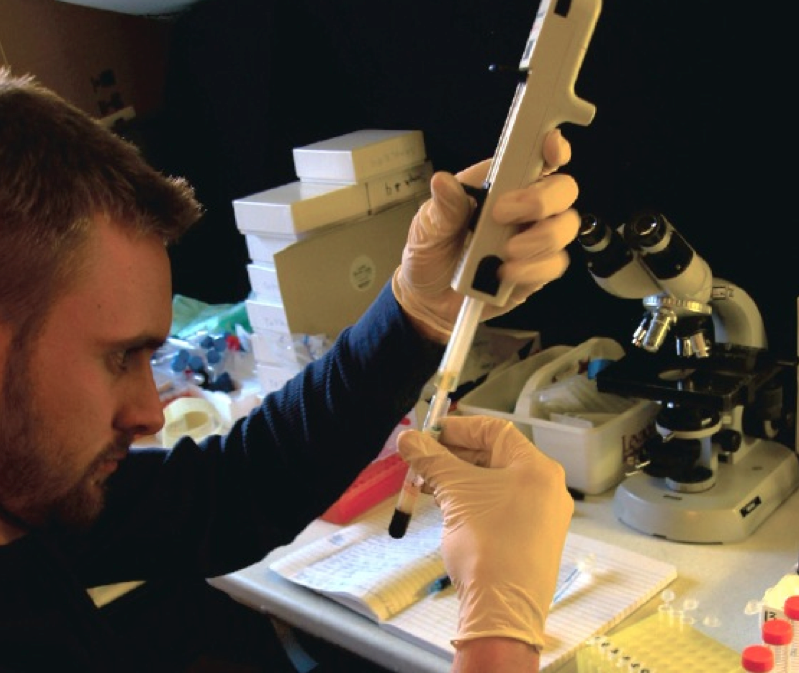

In the blood lab researchers prepared serum, plasma, and white blood cell samples for further analysis. Photo: Clifford Saron

By Sarah Sutherland

Last Friday we introduced you to the Shamatha Project, a comprehensive meditation study done on the psychological, physical, and behavioral effects of intensive meditation. The study, done in two three-month retreats by Researcher Clifford Saron and others in 2007, revealed some astounding results.

“The findings have taught us a lot about the benefits of meditation on our mental and physical health,” said Saron. So, how did researchers measure the results, and what did they discover?

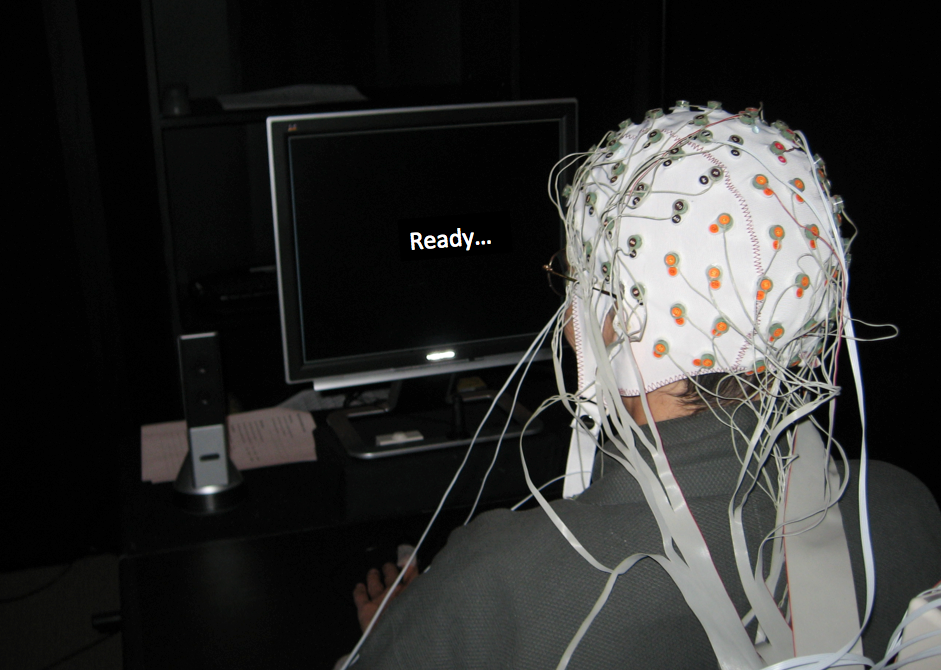

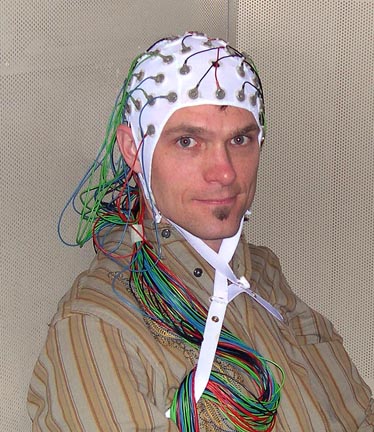

To measure the outcomes, researchers used a comprehensive approach, including interviews, computer-based experiments, physiological measures, behavioral measures, questionnaires, and self-reporting from participants before, during, and after the retreats. In some experiments, participants completed difficult computer-based tasks aimed at gauging attention and perception while their brain waves, heart rate, blood pressure, and other physiological indicators were recorded. At other times, facial expressions were additionally recorded as they watched disturbing images. In a separate, on-site blood lab, participants’ blood samples were collected and processed for later testing for telomerase, an enzyme that repairs genetic material lost during cell division, as well as various hormones and proinflammatory cytokines, which are molecules that trigger inflammation when we’re stressed.

In one key finding, the research team, in work led by Katherine MacLean and Baljinder Sahdra, has detailed how the retreat participants, compared with the control group, were better able to sustain visual attention through improved perceptual sensitivity and inhibit habitual responses. Importantly, the response inhibition improvements predicted psychological improvements as measured in increases in such traits as empathy, openness, and wellbeing and in decreases of depression, anxiety, and difficulty regulating emotions. When the control group entered the retreat, these same improvements became apparent. Many improvements lasted for months after the retreats.

To examine emotional changes from intensive practice, the researchers, led by Erika Rosenberg, studied how people responded to film scenes of human suffering. When responding to painful images, retreat participants showed a decrease in emotions such as anger, disgust and, contempt compared to controls. Instead, retreatants were more likely to respond to the suffering of others with sadness.

In looking at psycho-biological markers, the researchers, led by Tonya Jacobs and Elissa Epel and including co-investigator Elizabeth Blackburn, a molecular biologist who shared the 2009 Nobel Prize in medicine for her work on cellular aging, found increased levels of telomerase in retreat participants. In fact, levels of telomerase at the end of the first retreat correlated with an increased sense of purpose in life, as reported by retreat but not control participants. Also, participants who reported greater mindfulness had reduced stress hormones. Both findings point to a positive link between meditation, health, and possibly longevity, which Saron is eager to explore further.

“There is much more data to analyze and learn from,” he stated. And now, thanks to a recent $2.3 million Templeton Prize Research Grant from the John Templeton Foundation, he and his colleagues can take the Shamatha Project to the next level.

Read the third part in our series: Part III: Forging Ahead or Read the first post.