What Is the Meaning of Chöd?

by Alta Brown, Ph.D.

The symbolism employed in the Chöd practice is certainly exotic and is, by some, considered outrageous. An example of such symbolism is a part of some of the red feast practices. For instance, Red Feast No. 6 is described in this way:

Again oneself as Vajrayogini chops the corpse with the hooked knife. In a swirling ocean of blood, bones are planted down like a throne. From the tips of the bones, flesh is raised like banners. From these flesh bone and blood–those three fall continuously. Think that all the demons and obstructors enjoy for kalpas.

(Badan.ma.) [Garden of All Joy p.66]

The corpse that is being offered is that of the Chöd practitioner. The specific meaning of such symbolism will be discussed later on in the book Suffice it to say, that such an offering does not look like anything related to compassion. However the Chöd practice is, in fact, directly organized around the compassionate activity of feeding the demons, or exchanging oneself for the negativities that torment other beings. Exactly how this method creates the conditions for this exchange will be the subject of the following text.

Some commentators have claimed that Chöd is principally about cutting ego. While it is true the method is intended to do just that, it is also true that cutting the ego fixation is only the superficial, although necessary manifestation of a deeper intention, that is, to practice compassion at the most profound level.

The exotic symbolism of the Chöd method has often attracted practitioners simply by the power of its exoticism. It appears to them that Chöd is not going to be as irritating as continuously reciting mantras. It is exciting and frightening. Chöd is traditionally practiced in a charnel ground with corpses. That location, alone, is guaranteed to excite and terrify. Additionally the practitioner “calls” the very forms of harm that we are trying to escape, including, and especially, the confrontation with death. The first thing that Khenpo Tsultrim Gyamtso asked me after I had been practicing Chöd for a year, was whether I had practiced with corpses. Fortunately, I had. But I am not absolutely sure he would have continued to teach me Chöd if I had not had that opportunity. I suspect he might have decided that I was not a serious practitioner.

The fascination with exoticism usually only lasts for a short period. It is temporary. As the method does what it is intended to do, either the practitioner recognizes the power of the practice, or abandons it altogether.

Chöd is demanding and complex. As a ritual, it takes some time to learn. It is usually best to learn to master its intricacies in group practice, although, eventually many practice alone. However, it is not the complexity of the practice that may discourage a potential Chödpa or Chödma, but the fact that, immediately, from the time that the practitioner receives the empowerment and begins to practice, the world that their ego has created around them, begins to disintegrate.

Buddhist practice generally claims to release the serious Buddhist from the bonds of samsara, that is, everyday experience. But the reality of that release may be a great deal less attractive than they expect. Usually the release is experienced gradually. Chöd, however is not a gradual practice, and release may mean a startling acceleration of karma with its concomitant difficulties, such as the failure of relationships, physical problems or loss of job opportunities. What most Buddhists think they want is exactly the disintegration of their ego world, but when that occurs they may think “did I really want this?” For those practitioners who welcome the changes that practice brings, the development of compassion creates the possibility for an ennobled state of mind that was obscured by the limitations of the ego world they had previously inhabited. Though the acceleration of karma may be frightening, what the acceleration really means is that the karmic stream which has created damaging aspects of the practitioners ego world has actually come to completion. It will not be necessary to carry that karma into the bardo and subsequent lives. It will also remove whatever karmic based limitations that have obscured the compassion that leads to genuine bodhisattva activity.

Many claims have been made about the effects of Chöd practice. As I mentioned earlier, tales have been told about the crazy practitioners losing their minds as they dance and sing in the charnel grounds. Though it is true that some practitioners do dance and sing in the charnel grounds, they are not losing their minds, they are regaining their sanity as they engage in a celebration that includes dance and song. Khenpo Tsering Gyurme once explained to me that singing and dance magnetize the “demons.” Laughing, he said that the demons hear the celebration and think “oh, they are having a party. I think I should come.”

Chöd is a bliss practice. The demons are attracted by the radiance that is a direct result of this method of practice. As a former resident of Southern California, I have been suspicious of bliss, concerned that the bliss that results from practicing Chöd is closely related to the New Age practices that promise bliss but deliver a superficial, temporary high. I asked Khenpo Tsultrim how that bliss could help other sentient beings. He explained that a practitioner, experiencing bliss, attracts and is able to invite and welcome other sentient beings. This provides the opportunity to practice Bodhisattva activity. Still suspicious, I asked him how bliss is connected to intelligence. He said “the bliss unties the knots in our chakras so that our natural wisdom appears.” In a following section on Opening the Door to Space, I will explain how this works.

In Machig Labdron and the Foundations of Chöd, Chöd practitioners are described as “mad saints.” However, they are not mad because they are psychologically unbalanced, but because their developing insight transcends the accepted constructs of societal norms. The celebration in the charnel grounds is an example of such an activity which produces the radiance and joy a Chöd practitioner celebrates. Machig Labdron, the “original mad saint,” who created and promulgated Chöd, explains the joy in this way:

Because such love and compassion have not arisen in their mindstreams, people don’t realize that all sentient beings are their kind mothers. They hold onto them as friends or foes and the power of karmic action causes them to experience the immeasurable suffering of cyclic existence. Wouldn’t it be a joy if I could carry the suffering of all those mothers, and if all beings could have all of my happiness and virtue. In order to establish these mothers in happiness, what a joy it would be if, until cyclic existence is empty, their suffering and cause and effect of their sins all would ripen in me and these mothers would become abundantly happy. [Machig’s Complete Explanation p.150]

What Machig describes here is exactly the attitude upon which tonglen, taking and sending, is based. To claim that Chöd is Vajrayana tonglen is to explain that the compassionate joy Machig describes, transcends the “good feelings” which ordinary benevolence creates. “Carrying the suffering of our kind mothers,” and at the same time “offering all of my happiness and virtue” is the essence of tonglen writ large. In the Chöd practice the offering of one’s body is the fundamental gift that is sent, while at the same time, the suffering of all sentient beings is taken on. This exchange is so much more profound than the simple intention to alleviate the pain that individuals suffer, while simultaneously taking on that pain. The raw, immediate, global quality of the Chöd exchange distinguishes it from the ordinary tonglen practice. It is the dimension of that exchange which defines its vajrayana character.

Before I continue, I would like to explain exactly how tonglen is understood as a practice. For the ordinary practitioner, tonglen is a meditative awareness discipline in which the meditator breathes in the pain of a set of beings whose suffering they may share. On the out breath, the meditator breathes out the radiance of their enlightened intention. This is potentially a relatively simple exchange. However, in its most profound manifestation, it can deepen into what I have described above as vajrayana tonglen.

The celebration in the charnel ground finds its origin in the intense joy that the radiance of the transmutation of the suffering of sentient beings creates.

Now one might ask exactly why Chöd practitioners carry out the Chöd ritual in a location such as a charnel ground. What is it about a charnel ground that creates the appropriate conditions for the Chöd feasts?

There are at least three reasons that this location is so important. They are as follows:

- Chöd practitioners practice in a charnel ground for the same reason that they practice with corpses. These practitioners understand that the mind of the person who has died is still present and must be reminded that, in death, they are not the object with which they have been previously identified, their body. There is an intelligence and awareness that will continue even as this body is destroyed.

- Chöd practitioners invite demons to the feast. What better place than a charnel ground to encounter these forces. The following is the way in which charnel grounds have been described in the past centuries: We can imagine the scene: bone and skulls litter the ground, smoke and stench of burning flesh fill the air. Wild dogs and hyenas roar around, snarling and cackling, as they scavenge among the dying embers of the funeral pyres, crows pick at the entrails of half burned corpses and vultures circle overhead. Tigers and lions and other wild animals prowl and roar in the nearby forests. [Luminous Emptiness p.302]

- Even more terrifying is the presence of demons and ghosts who continue to haunt the remains of their former bodies. The dismembered corpses, the flesh and blood, the skulls, bones, the internal organs, the flayed skins represent everything we would rather avoid. They reveal areas that disgust and revolt us, and the secret, sensitive parts that we do not want to look at or expose. Here we find everything we reject as having nothing to do with our spiritual nature, yet is the source of our energy and must be recognized and accepted . [Luminous Emptiness p.303]I’ve been told that the crucial test of Chöd maturity is practice in the charnel ground. The question arises if there is no such environment available, and no corpses a practitioner is allowed to include in their practice, how is it possible to do such a practice?

Fortunately, I have been assured that there is a more immediately available charnel environment: As Trungpa says “ The world is our charnel ground, everything is continually dying and being reborn. It is a place of birth as well as a place of death. It is the ground of transmutation.” [Luminous Emptiness p.303]

Since the transmutation of demons is exactly what Chöd is organized to achieve, it is clear that the charnel ground is exactly the appropriate location for the celebration of the exchange of suffering for the luminous brilliance of ultimate compassion.

When I was asked why I was motivated to learn and later teach this practice, I explained that this era is experiencing an explosion of negative energy and the suffering these energetic demons create. Chöd is the practice of compassion that directly recognizes and transmutes that negativity. At the level of awareness, beyond the safety of conceptual formulations, Chöd welcomes the demons and feeds and befriends the energy itself.

Chöd works with the raw suffering on its own grounds, in its own environment. For this reason, it is the appropriate time, the darkest of times, for the Chöd practice to appear to the spiritual consciousness of a tormented world.

Join Lama Alta August 9-15, 2023 for Chöd, or as part of the Mahayana Summer Seminar!

About the Author: Dr. Lama Alta Brown

About the Author: Dr. Lama Alta Brown

When Trungpa Rinpoche arrived in Boulder CO, Lama Alta immediately connected with him and studied as his student. After Trungpa died she studied, and continues to study, with Khenpo Tsültrim Gyamtso, Khenchen Thrangu Rinpoche and Dzogchen Ponlop Rinpoche. She was introduced to Chöd by Khenpo Tsültrim at the monastery in Pullahari, Nepal. He supervised her practice while she did an individual 3-year Chöd retreat. Eventually, he began to send her students. She has been practicing Chöd since 1996 and has been teaching this practice since 1999.

Dr. Brown completed her doctoral work at the University of Southern California, specializing in Buddhist Ethics. She wrote her dissertation on Mediation as a Bodhisattva’s Practice of Peace. She subsequently taught at the University of California at Berkeley through The Graduate Theological Union where she emphasized aspects of Buddhist ethics. She also taught for The Semester in India program through Antioch University and, for five years, taught weekend retreats through The Immaculate Heart college center at The Retreat Center La Casa De Maria. Dr. Lama Alta Brown currently leads an international Chöd sangha. Much of her training in compassionate activity developed out of her experience as the mother of six children.

References:

Luminous Emptiness

Understanding the Tibetan Book of the Dead

Francesca Fremantle

Shambhala

Boston & London 2001

Machig Labdron and the Foundations of Chöd

Jerome Edou

Snow Lion

Boston & London 1995

Machik’s Complete Explanation

Clarifying the Meaning of Chöd

Expanded Edition

translated and introduced by Sarah Harding

Snow Lion

Boston & London 2013

The Garden of All Joy

H.E. Jamgon Kongtrol Lodo Thaye (the Great)

translated by Lama Lodo Rinpoche

KDK Publications 1993

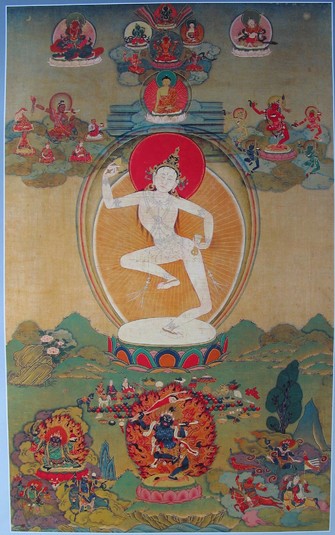

Photo Credit: Himalayan Art Resources #77175 with gratitude

About the Author: Dr. Lama Alta Brown

About the Author: Dr. Lama Alta Brown