A Troubled World: The Greed, Hatred and Delusion Report

By Kevin Griffin //

“Even if bandits were to sever you savagely limb by limb with a two-handled saw, he [or she] who gave rise to a mind of hate towards them would not be carrying out my teachings.” – “The Simile of the Saw” from The Majjhima Nikaya

Sometimes when I’m reading or hearing the news, I feel as if my limbs are being sawed off. Maybe the “news” should be called “The Greed, Hatred, and Delusion Report.” How to live happily in this atmosphere of conflict is one of the great challenges we face.

My practice opens me up so that I can’t numb myself to the suffering of the refugee family drowning in the Mediterranean as they try to escape war and oppression; I can’t escape the anger that arises when I see a black man shot down in the street for a petty crime; I can’t hold down my resentment at the CEO who walks away from a crumbling company with a golden parachute; and I can’t restrain my disgust when I see advertisements that promise happiness with the purchase of a new car. But the dharma tells me that I mustn’t allow myself to be swept away by these feelings or I will be replicating the very qualities that I deplore. The peace protestor who spits on the soldier returning from war acts on the same hatred that drives that war. As in “The Simile of the Saw,” the Buddha challenges us to take another way.

There are two things to consider when faced with The Greed, Hatred, and Delusion Report: my inner response and my outer response. On a daily basis, if I am going to be an engaged citizen, I must deal with all the feelings that arise around The Report, the anger, the wish to shutdown, the resentment, fear, and disgust—and the heartbreak. At the same time I must consider how to respond in the world. Mindfulness and the Brahmaviharas, loving-kindness, compassion, sympathetic joy, and equanimity, can offer some vital tools and guidelines for these considerations.

In the Dhammapada, the Buddha famously says, “Hatred never ceases by hatred, but by love alone is healed. This is the ancient and eternal law.” Cultivating loving-kindness gives us another way of responding to the hatred we see. With love and compassion, with joy and equanimity. These are the antidotes. Love inside and love outside. Compassion inside and compassion outside. Joy inside and joy outside. Equanimity inside and equanimity outside.

Love inside is the wish for all beings to be happy, whether they are kind or wise or not. This protects my own heart from the poison of hatred.

Love outside means my actions are motivated by love, even if that love is fiercely protective.

Compassion inside means I see my own agony when reading The Report, and I bring an attitude of kindness to myself; and I know that even the oppressor suffers, so I bring compassion to him or her as well. Thich Nhat Hanh’s remarkable poem, “Please Call Me by My True Names,” expresses this compassion powerfully in evoking images of the Vietnamese boat people, a pirate who rapes a girl and the girl who is his victim. Both deserve our compassion he says. The pirate’s heart is closed, his spirit crushed by war’s brutality. He can’t even feel his own suffering, he is so numb. The girl’s heart is broken as she throws herself into the sea, unable to live with the shame and trauma.

I try to think of this teaching when I see the cruelty on the front page. I try to remember that those who act hatefully and fearfully hold those very feelings within, carry hate and fear in their hearts every day. Even though I recoil from their actions, I remind myself that they are trapped in their own suffering, lost in a brutal worldview that plagues their minds and corrupts their entire lives. This is how I can arouse compassion for the dictators and oppressors of the world.

Perhaps the greatest challenge to compassion is our desire to turn away from other people’s pain. The Report shows so much ordinary suffering that it can become overwhelming to take it in. Hunger and oppression; addiction and disease; poverty and famine. With seven billion people on our planet, it’s inevitable that virtually every possible condition will be present. Besides, we have to recognize that the economics behind The Report want to emotionally trigger us in any way that will maintain our attention. At some point, we have to protect ourselves compassionately, by stepping back from all this information.

The point of understanding that the news is a Greed, Hatred, and Delusion Report is so that we don’t have to read every detail of every story of misery. We already know that’s what we’re going to be seeing. The Buddha’s teaching on the Middle Way suggests that we need to figure out how to be informed without being overwhelmed.

Joy inside is the appreciation of life, even with its suffering. After all, why do we hold life so dear if it holds no joy? When we discover the safety of the heart, the peace of the well-trained mind, and the beauty of pure awareness we see that there’s no need to add anything to life. It is inherently rich and fulfilling.

Joy outside is there in nature, in friends, and love. In art and music, literature and film. The Report depicts a world riven by conflict and suffering, but if this were the whole of the story, ours would be a world hardly worth saving. But we know this is only a part of the story, the part that gets our attention. Most of the moments of caring and connection, of generosity and sacrifice, of beauty and inspiration never make it into the Report. The Report tells us about the anomalies—the “man bites dog” stories—and never mentions that most people are living lives of peace, harmony, and love with their families and neighbors—and dogs. And so, The Report inflates the conflicts so that they gain outsize importance and significance.

The practice of joy reminds us to pay attention to the quieter events, the ones that more truly define our lives.

Equanimity inside comes from the mind training of meditation. The nervous system itself changes with deep practice, no longer so easily disturbed by thoughts and feelings, by fears or regrets.

Equanimity protects the other Brahmaviharas so that love doesn’t become foolish and blind; compassion doesn’t burn out or shut down; joy doesn’t overload into mindless elation.

Equanimity outside doesn’t imply passivity or apathy. We still engage with politics or economics or any other social issue. We just do it with the larger understanding that there is no permanent solution to impermanent events; that no perfection exists in an imperfect world; that all humans are subject to the three poisons. As Buddhists we aren’t putting ourselves above anyone or suggesting that we are different or better than anyone, only that we have changed our view of the world and our intention to act in it. We at least want and hope to overcome the poisons, even if we fall short a good deal of the time.

At some point, though, we must simply accept all that we see in The Report. We can’t control the world or the people in it. It’s this realization that the Buddha expresses at times when someone refuses to understand his teaching: “Now is the time to do as you think fit.”

Excerpted from Kevin Griffin’s forthcoming book Living Kindness: Buddhist Teachings for a Troubled World

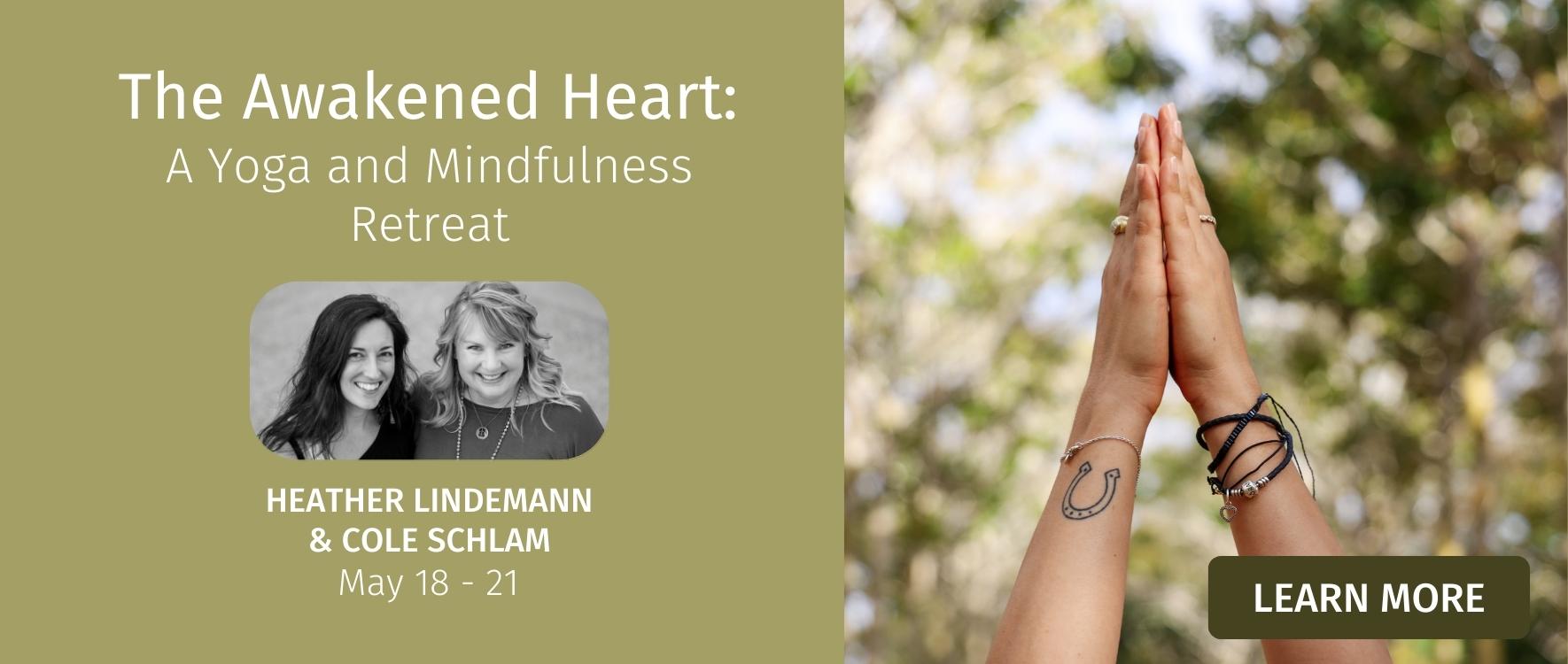

Shambhala Mountain Center hosts One Breath, Twelve Steps: Buddhist Contemplative Practices for Recovery with Kevin Griffin, May 5–7, 2017

About the Author