The Architecture of Love

By Katharine Kaufman //

“Living things must disappear, everyone you meet inevitably splits.”

— from the Butsu Yuikyôgyô (Jp.) or Buddha’s Last Admonitions Sutra*

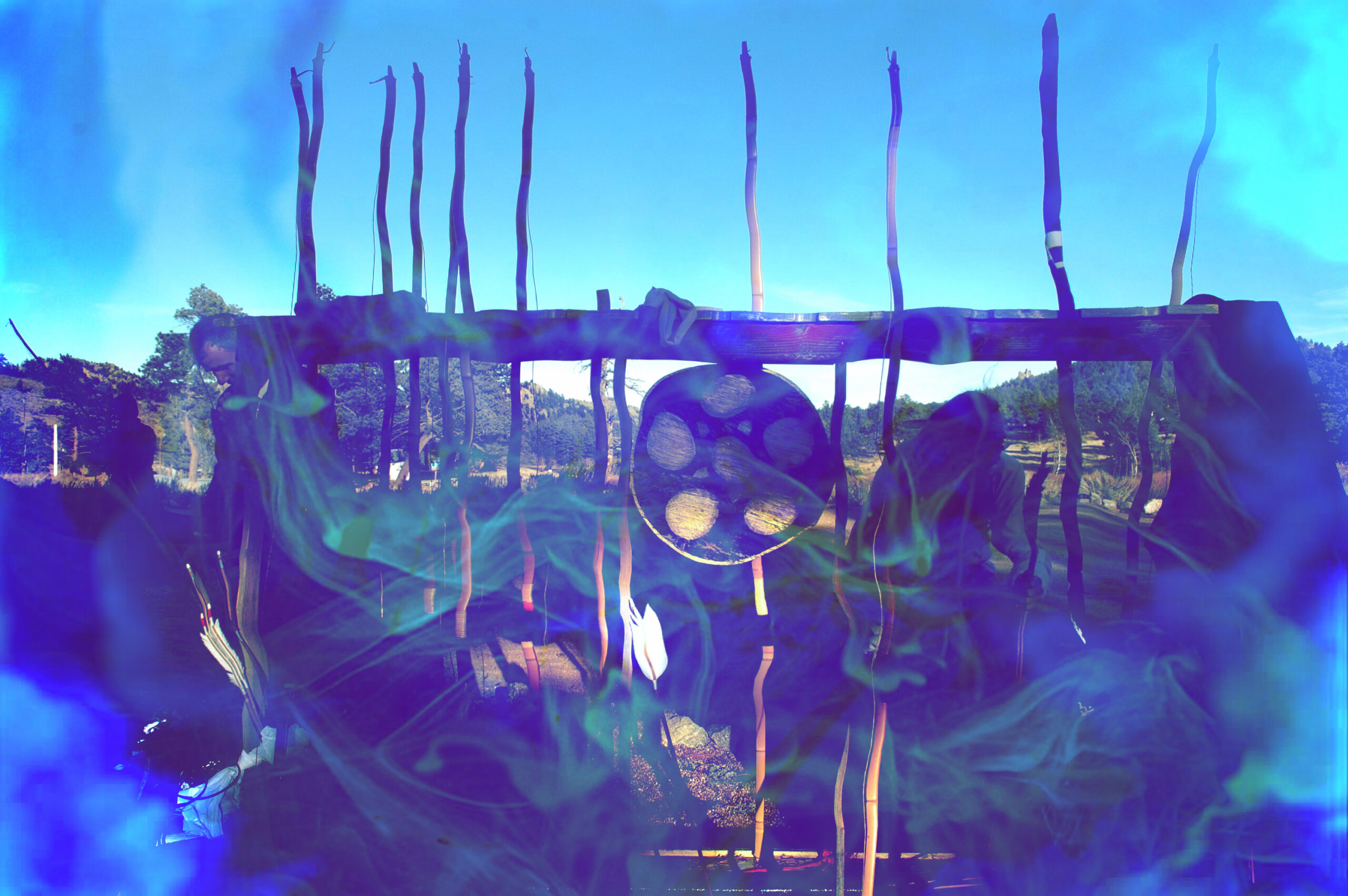

After Trungpa Rinpoche died Joshua Mulder was asked to care of Rinpoche’s relics. Joshua, along with many, designs and builds the Die Zauberflöte of Stupas. A stupa is a mound of rocks to serve as a home for bones, ashes; a cairn that tells me where to go next on the path I am walking on, especially if it’s foggy or for whatever reason I can’t see ahead. The stupa is a body— my body, the body of the Dharma. A place to practice, and in my case, a place to get warm.

January. If the cover of my New Yorker magazine is any indication of what’s to come, it’s going to be a tough month. At Shambhala Mountain Center Joshua leads us up the path to the Great Stupa of Dharmakaya, pausing to remind us to open our senses to the phenomenal world. Damaris, my friend from Oregon, says every time she hears the words “phenomenal world” it gets her. The students from Chapman University expect to go immediately into the stupa for the warmth, and destination. I can feel them like racecars at the gate. They don’t know that there are a few gates to consider before we can enter the sanctuary—invitations, requests, conversations, teachings. They also don’t know how to tuck their gloves into their sleeves, some don’t wear hats; sneakers are soaked, coats flap open. We walk around the massive stupa. And then we walk around it again. It’s so cold that when Joshua asks if we have questions I hope no one has questions. The students are bright, curious and Joshua speaks closely to them. They hone in and listen. Joshua stops at each of the gates, yellow, green, red, blue. He says he knows we are all going to die but not him. It’s kind of a joke but not. We touch our heart center, pound our chests with our fist, and repeat, I am going to die—this body—me. There’s a small crack in the solid, frozen nugget of my heart and I look around. Are people getting this? Joshua walks quickly to the next gate.

Later, in the car to the airport Damaris says that is exactly how she feels. I know you will die but not me.

Sixteen years ago in April I walked up to the Stupa with Joshua and Yoga teacher, Richard Freeman. The giant sitting Buddha inside the Stupa was in process of becoming. Joshua asked Richard about the alignment of the Buddha. Richard handed me his backpack and looked closely. A little less full in the right buttock, Richard says. Joshua runs up to the Buddha with some tool that looks like an axe, climbs up his legs and bam—bam—bam, takes a bit off the right butt of the Buddha. He climbs down again. Richard and Joshua stand together looking at the Buddha. Yes, that’s better, Richard says. Look at the left shoulder compared to the right. If the right leg is crossed over first than wouldn’t the left shoulder be slightly higher? Off goes Joshua, he raises the axe and bambambam, he cuts away at the Buddha. They stand together, silent, gazing at the unfinished Buddha; an enlightened Salvador Dali meets Krishna.

Joshua invites people to create art in the Stupa, to dance and sing opera and read poems. The Stupa is a place for expression, for the people. When asked what his best moments are he says, when people are practicing on all floors.

~

When family members leave, or die, everything shifts. Not a piece of white paper falls off the desk and slides across the floor. The tectonic plates shift. When I look up and pause from what I am involved with my default is to a low, uninterested stare. Last month I took a sample of a brownie at Whole Foods and the person behind the counter only looked at me. Oh, I’m sorry, are these not for us? I said. It’s OK, honey, she said. It’s fine. You’re OK. Take as many as you like.

~

Every day at Shambhala Mountain Center I am hugged, people talk with me, and listen, and offer kind understanding. We have deep conversations immediately. For two hours Melissa asks what do I want for every retreat I teach there. I want crayons if Heather assists and only pens if she doesn’t. I want tea treats the second to the last day at 3:30. I’ll bring my own flowers for the women. The best room is 203 for the space, and the bed. 206 is next, for the view. She writes this all out. I see my old friend David. He grew up in the town next to mine and I yell at him he owes me a dollar. Here’s your dollar he says, and there is Damaris. They got in at 2am and slept in an empty room. As I am speaking to David, Barry hands me a note written by Kim, who I didn’t even know was in the country. She is practicing in a closed-off area on the other side of the land. Could I come by and give you a quick hug at least, she writes. Barry gives a hilarious and poignant Dharma talk. Barney offers solid advice. And Michael gives me a little handmade book with haikus, some in Japanese. Damaris and I teach together and Michael and I teach together. We trade back and forth. When I mention the generosity, the love, someone says, this is your family.

The stupa is the center of the mandala. During the women’s retreat we walk up together and the women speak with confidence. No matter what is going on, whether I am getting a massage from Halka, comforting a sobbing student, or writing in my journal before bed the Stupa is the center of this place—lights me up. It disappears my discursive mind.

~

Usually when a student comes to my class at Naropa and describes herself as, We’re all one. It’s all about love. I think, good luck with that philosophy. What happens when, as Leonard Cohen sings, “Love itself walks out the door.” Yes and Love is everything, consciousness itself. “I am he as you are he as you are me and we are all together.” (Somehow the Magical Mystery Tour comes into this paragraph). I slowly learn how I have added to your suffering which allows me to begin to honor difference—to see myself as you.

If we are altogether then maybe I wouldn’t have to try to be kind. I wouldn’t need to be afraid, or mis-trust. I believe you. I think the best of you.

If I have a choice I’ll return to love.

~ o ~

*The epigraph line was given to me by Michael Wood, who offers the following commentary: “It comes from the Butsu Yuikyôgyô (Jp.) or Buddha’s Last Admonitions Sutra (佛遺教経). The complete phrase (which my calligraphy teacher selectively truncated) is 生者必滅会者定離 (sheisha hitsumetsu esha jouri) or ‘Living things must disappear, everyone you meet inevitably splits.’ ”

Also coming up:

- Inside (and) Out: Meditation and Yoga for Everyone with Katharine Kaufman, July 12–15, 2018 — click here to learn more

- Women’s Summer Meditation and Yoga Retreat with Katharine Kaufman, August 1–5, 2018 — click here to learn more

About the Author